GPU Driven Occlusion Culling in Life is Feudal

In 2016 I gave a small talk in Dublin, Ireland about the subj, here are the slides and below you can find a more or less human-readable version of the slides above.

Table of contents

- A quick history of the occlusion culling algorithms

- Occlusion queries

- Software occlusion culling

- Coverage buffer

- GPU driven occlusion culling with geometry shaders

- GPU driven occlusion culling with compute and DrawIndirect / MultiDrawIndirect

- Occlusion queries vs Software occlusion culling vs Coverage buffer

- Occlusion culling with geometry shaders

- Occlusion culling with compute shaders

- Use cases and demos

Occlusion queries

This is the most ancient and used method - you render your scene in a special rendering mode with either D3D11_QUERY_OCCLUSION or GL_ARB_occlusion_query and after a few frames it will return you the amount of pixels pixel shader was invoked for.

Summary

They are good because:

- Fast on the GPU

- Accurate enough

- Can save both CPU and GPU time because it is possible to skip CPU-side draw calls

- Can be used for shadow blockers (in theory)

They are bad because:

- Require additional draw calls

- They require separating occluders from occludees and structruring the scene carefully

- They have high readback latency (up to 5 frames in extreme cases)

- Even higher in case of multi GPU setups

- Pixel-to-visibility correlation is not obvious and awkward

Software occlusion culling

This technique uses software rasterization to render occluders to the downscaled depth buffer and test occludees against it. Everything is done on the CPU.

The most recent paper on this is from Intel.

Intel suggest an efficient SIMD-optimized way to rasterize and test boxes agains a depth buffer.

Summary

It is good because:

- Occlusion testing results are available immediately, frame latency is zero

- It saves GPU time at the cost of the CPU time

- In theory can also save some CPU time IF skipped draw calls were more expensive then rasterization, but that is probably unrealistic

- Scales well with multithreading

It is bad because:

- Software rasterization is SLOW on the CPU

- can’t use for shadow blockers, too slow

- can’t have too much occluders, rasterization is slow

- can’t have too much occludees, testing is not fast either

- Due to the fact above suits bad for dynamic scenes

- Bad for consoles, because requires high-end CPU (a selling feature for Intel?)

Coverage buffer

There’s not much to say about it except that it is almost the same as software OC. The only difference is that instead of rasterizing occluders it reads the depth buffer from the GPU, downscales and reprojects it and tests occludees against it.

Also, it reintroduces the nasty frame latency.

It was pioneered by Unreal in 1997 and later used in production by Crytek

Reprojection

GPU readback has high frame latency, so in order for this to work the depth buffer values must be unprojected using the previous frame matrices and projected back using the current frame matrices - this step is called reprojection.

The main caveat is that reprojection usually leaves big gaps in case of fast camera movements and various holes.

In order to fix them a simple dilation filter is applied, though it does not fix the gaps on the screen edges (note the gap on the right).

Summary

It is good because:

- It is faster on CPU then software OC

- The whole world acts as a single occluder making it potentially more efficient

- Works better for outdoor scenes

- Everything else is the same as in software OC

It is bad because:

- Reprojection leaves gaps and holes

- Can’t rely on depth that is 3-5 frames old

- Can’t fully rely on reprojection

- Fast camera movement will leave big gaps that will occlude nothing

- Depth buffer readback has the same latency as occlusion queries

- Everything else is the same as in software OC

Occlusion queries vs Software occlusion culling vs Coverage buffer

Here’s a small comparison table for methods mentioned above.

| X | Static world | Dynamic world | Indoor | Outdoor | Shadow blockers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Occlusion query | OK | Bad | OK | Bad | Yes |

| Software OC | OK | OK | Good | OK | No |

| Coverage buffer | OK | OK | OK | Good | No |

Occlusion culling with geometry shaders

Arguably the first fully GPU driven occlusion culling method, pioneered by Daniel Rákos

The main idea is to render occludees as points (with bounding box data as attributes) and:

- Vertex shader checks the bounding box agains the frustum

- If visible, sends the vertex to the geometry shader

- Geometry shader tests the box agains the downscaled depth buffer in a similar way software OC does

- If test is passed then GS emits the primitive

- StreamOutput or TransformFeedback captures the emitted data

Summary

Pros:

- It does frustum culling as a side-effect

- Zero CPU cost

- Does not require any kind of complex scene management

- Zero frame latency

- Handles lots of objects

- Works well for dynamic scenes

Cons:

- Needs some extra draw calls

- Need to predict buffer sizes somehow to avoid extra memory consumption

- Kills vertex cache (though can be fixed)

- Still uses a downscaled depth buffer

Occlusion culling with compute shaders

The general idea is to implement software OC using the GPU for rasterization and testing, huh.

This technique was pioneered by NVidia

It works this way:

- A simple pixel shader is used render occluders to the depth buffer

- This shader knows object ID and has a writeable buffer attached that stores object visibility

- Pixels that pass depth test write visibility flag to that buffer by object ID

- A compute shader is dispatched for all objects

- It reads visibility flag from the buffer

- If the flag is true it appends arguments for DrawIndirect / MultiDrawIndirect call

- DrawIndirect / MultiDrawIndirect everything!

- This also trivially extends to the Coverage buffer approach

- Just use and optionally reproject depth buffer from the previous frame

- Adds exactly 1 frame latency, which is usually acceptable

- No need to separate occluders and occludees - rasterization is dirt cheap, earlyZ also speeds things up

Summary

Pros:

- Zero CPU cost

- All the pros from the software occlusion culling or software coverage buffer

- Zero frame latency for OC, 1 frame latency for CB

- Coverage buffer might not need reprojection step due to low latency

- Scales extremely well

- Possible to use BVH which makes it even faster

- Shadowmaps? Why yes! Can easily use for shadow blockers

- DrawIndirect does not kill vertex cache -> no performance impact there

- Trivial to implement

- Extremely precise, no need to downscale at all

Cons:

- DX11+

- Indirect rendering is usually slower then usual rendering

- Requires that everything is rendered with instancing and batched efficiently, otherwise not efficient

Use case: forest rendering in Life is Feudal

- We use a quad tree to split the whole forest into cells

- Each cells is used as a bounding volume for an area covered by trees

- Each cell is an occlusion volume

- Cells are rendered as a bounding boxes

- Cells are dynamic

- Trees are dynamic

- Each tree can be cut, burned, grown, etc

- Massive tree destruction possible: forest fires, damage from siege machines, etc

- Forest is HUGE: 500k trees is a common ingame situation

- For forests we use a coverage buffer approach

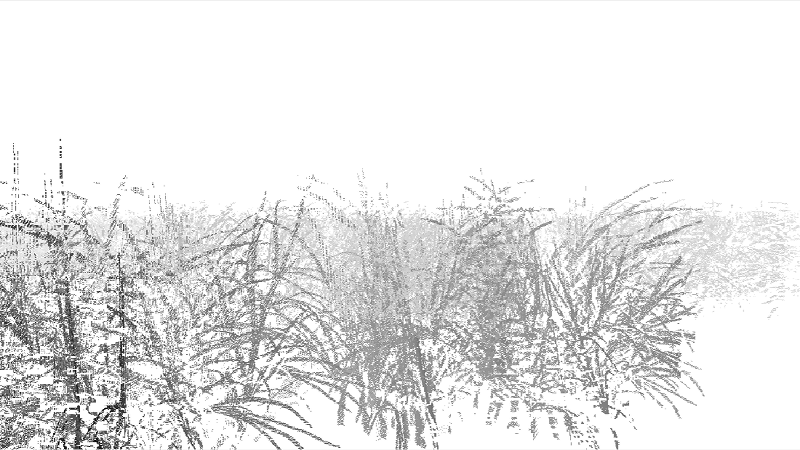

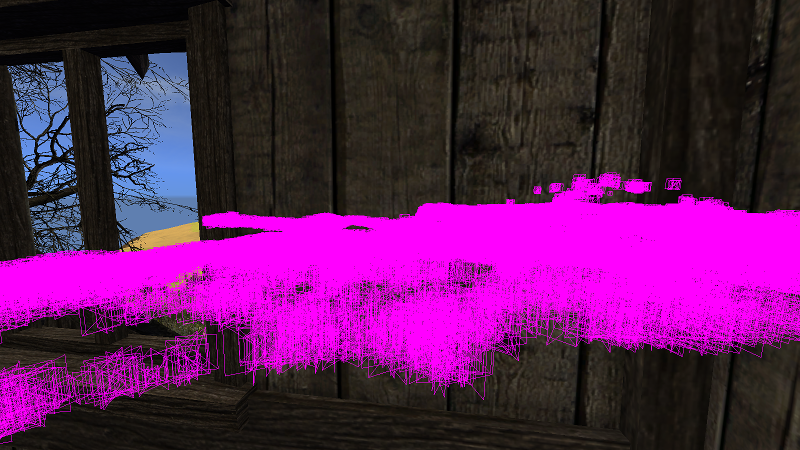

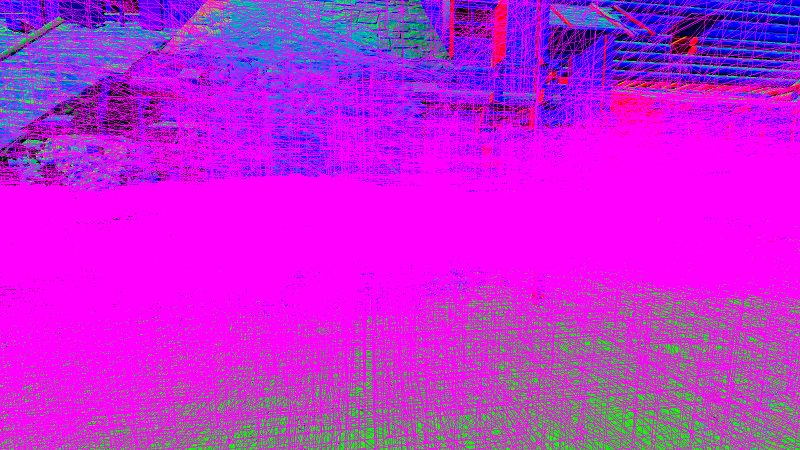

Here is the worst case when everything is visible and nothing is culled:

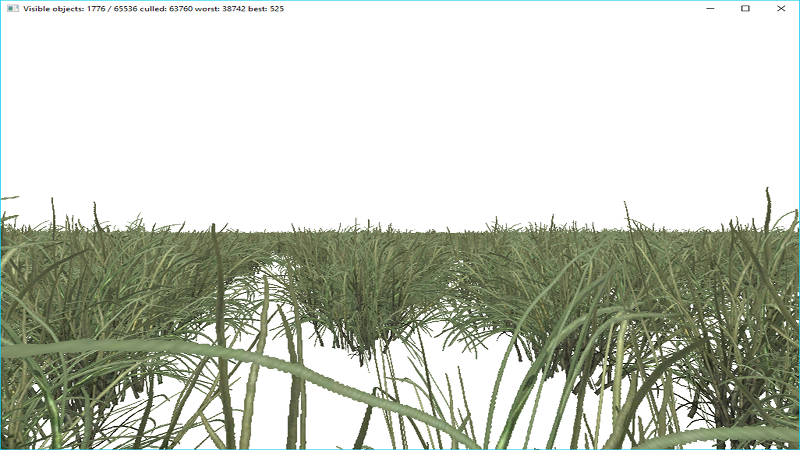

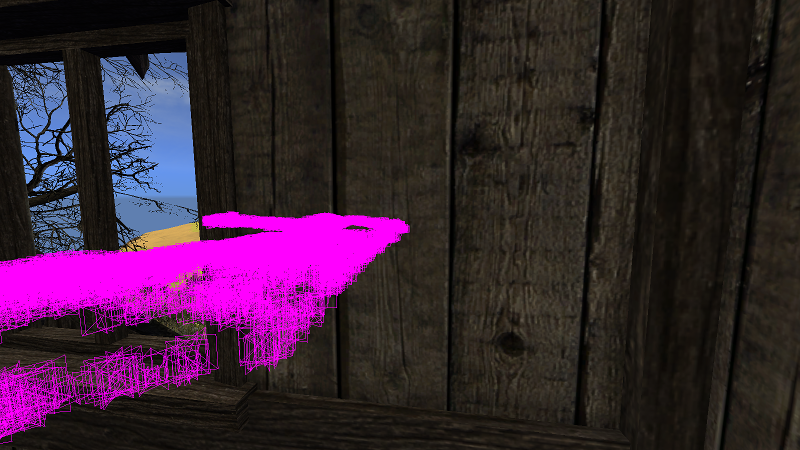

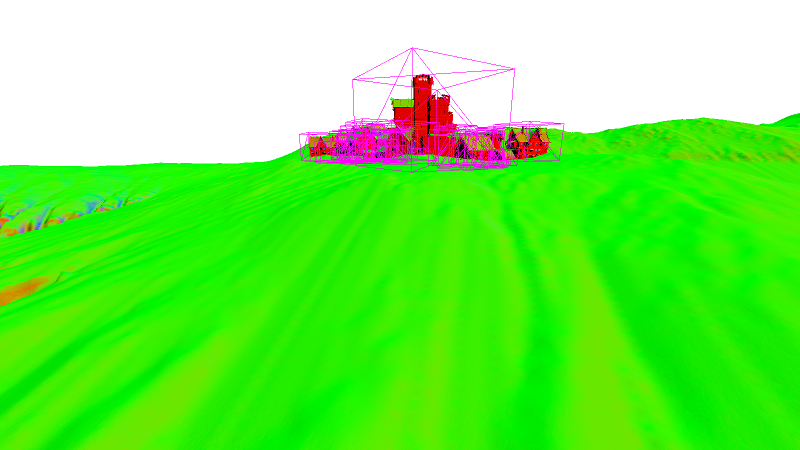

Here is the best case when only a small fraction is visible:

And here is what was actually rendered with occlusion culling on and off:

Use case: static object rendering in Life is Feudal

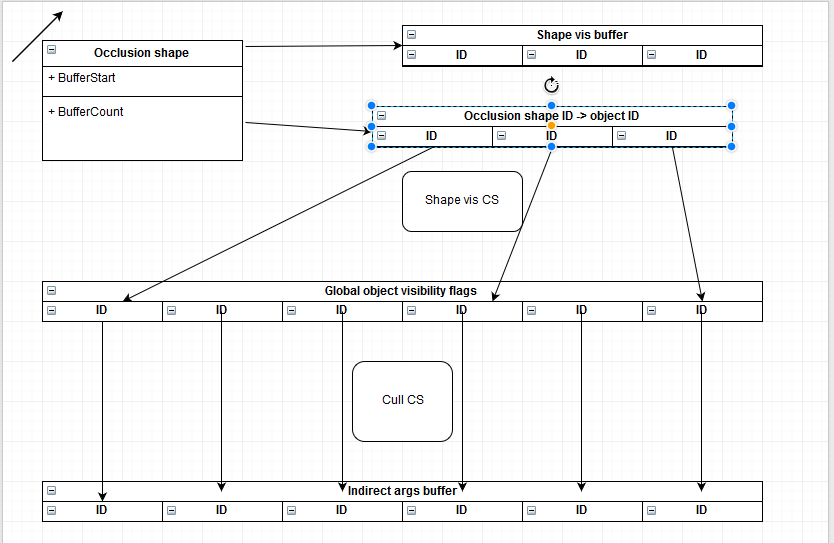

- Works almost the same way as forests, but much more complex

- Need two separate IDs for every object - for occlusion shape and object itself

- Each shape stores a list of objects it covers

- There’s also a global buffer with object visibility

- Need indirection to map objects inside the shape to the global object buffer

- This step is VERY counterintuitive, but manageable

- Also keep an eye for an overdraw

- Try to minimize occlusion shape count, use big shapes to cover lots of objects

Here is a small diagram that shows all the relations between objects/shapes/IDs:

Managing occlusion shapes

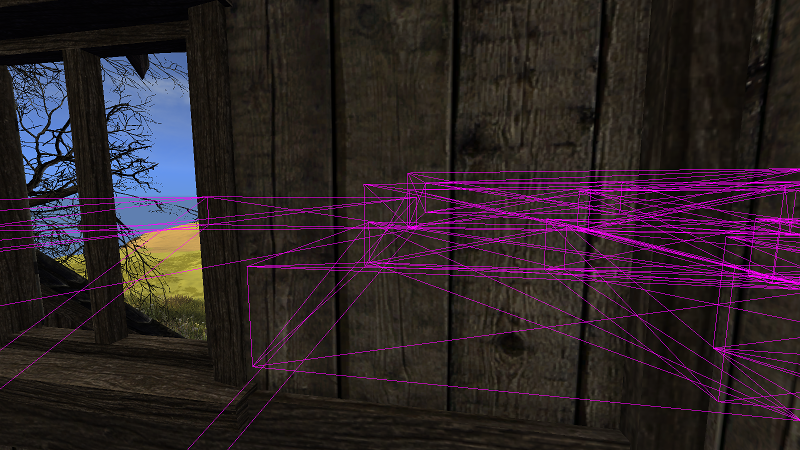

It is a very good idea to have big occlusion shapes that cover lots of objects. In LiF game our ingame objects are modular and made from smaller parts, so it is vital for us to cover as much as we can with a single shape.

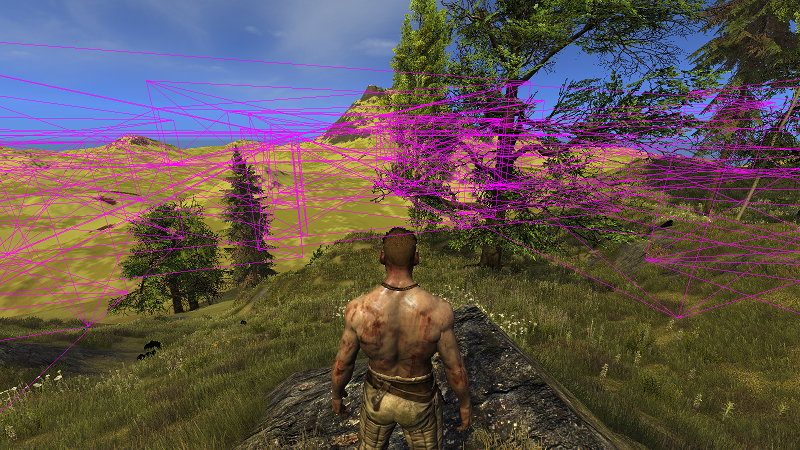

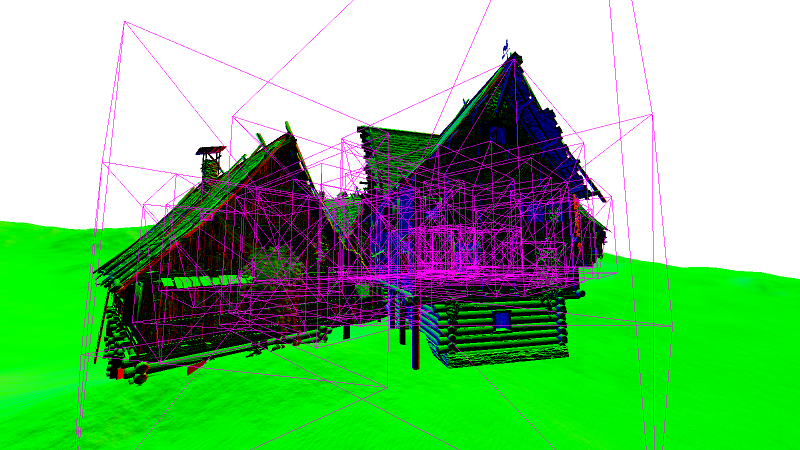

And here’s the mess we’ve had on early implementation stages - due to the overdraw it gave us a negative performance impact!

Bounding box merging

Our occlusion shape management code allowed us to introduce a nice optimization we call box merging.

- Main idea: distant objects can share one big bounding box

- Because their screen projection is usually small and small boxes are usually bad

- And due to the same reason the error introduced by box merging is acceptable

- Implementation is trivial

- Just add boxes for distant objects that are close enough to each other

- Then use the produced box to cull all containing objects

And here’s how it looks in practice:

Conclusions

- GPU driven occlusion culling is a must!

- Can easily switch between coverage buffer / conventional culling

- Low overhead and high scalability

- A great improvement over the previous methods

- DX11 demo source code: https://github.com/bazhenovc/sigrlinn/blob/master/demo/demo_grass.cc

References

Secrets of CryEngine 3 graphics technology

Bug

Here’s a nice DrawIndirect-related driver bug that I’ve found worth sharing: